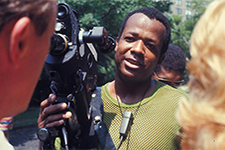

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One [Blu-Ray]

|

There are so many levels of meaning in William Greaves' oddball 1968 experimental hybrid Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One that it's hard to know where to begin deconstructing it—or if deconstruction is even a possibility. Ostensibly about a film crew conducting screen tests of a scene of marital meltdown in New York's Central Park West, the film is simultaneously a documentary about acting, a documentary about the nature of power relationships on a film set, a unique snapshot of American sensibilities in the turbulent late 1960s, and a sly investigation of the nature of reality and illusion in the cinematic apparatus. This last characteristic is the film's most intriguing and perplexing and also the one in which Greaves appears to be most interested. At the time the film was made, Greaves had already long since established himself as a Renaissance Man who had become a minor star in "race movies" of the late 1940s, which he then parlayed into a career teaching acting workshops before transitioning behind the camera to become a rare black filmmaker in both cinema and television prior to the Civil Rights era (he earned an Emmy in the late 1960s for his work on the groundbreaking PBS series Black Journal, which he was hosting when he made Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One). Thus, Greaves had experienced the creation of cinema from virtually every angle, in front of and behind the camera, and in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One he sought to combine the unadorned tenets of cinéma vérité-style documentary filmmaking with self-reflexive meta-commentary about the very nature of cinematic creation. The title of the film—which alone is enough to pique the curiosity of anyone interested in a cinematic experience outside of the ordinary—is derived from the awkward term "symbiotaxiplasm," which was coined by social philosopher Arthur Bentley to refer to everything that takes place in any environment that affects and is affected by human beings. In other words, it is a word that takes into account the complex interrelationships among material objects, events, and human beings. Greaves boldly inserted the word "psycho" into the middle of Bentley's term to emphasize the psychological ramifications of these interactions, and his film is a brief portrait of just what a "symbiopsychotaxiplasm" might look like. (The "Take One" part of the title refers to the idea Greaves had of making multiple films out of the footage he shot, but that never really happened. In 2005, with the help of Steven Soderbergh and Steve Buscemi, he produced Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take 2 1/2, which brings back two of the actors from Take One.) The majority of the film was shot in Central Park with three simultaneous cameras following an indie director (played by Greaves) who is shooting screen tests with various actors playing a husband and wife having a bitter argument. The argument itself is rather poorly written and hinges on the wife accusing the husband of being a latent homosexual. Interestingly, even though we are hyper-aware that this is all staged—a screen test, no less, not even a film sequence proper—the drama-within-the-drama is strangely moving because it represents such raw emotions in the making. It can be jarring when the scene is broken up by the camera running out of film or Greaves calling "cut." The drama of the documentary itself revolves around a secret mutiny by the rest of the crew, who feel that Greaves' film is a joke and that he has no idea what he is doing. There are several scenes in which the crew members gather together to discuss their dissatisfaction, self-consciously filming the conversation with the acknowledged notion that it might very well wind up in the film itself. Thus, we are faced with a fundamental question: Are they complaining about the fictional film-within-the-film or the film itself? Or, are the two inseparable since they exist on differing levels of reality within each other? Greaves underscores the multi-dimensional nature of cinematic reality by often employing split-screens to give us up to three simultaneous images of the same action from different vantage points, which shows how camera placement and the person operating the machine can make a world of difference in terms of what is captured. Such ontological head-scratchers are central to Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One's genius because Greaves' film(s) draw(s) you in, rather than constantly keeping you at arm's length as so many other experimental and avant-garde films do. It's surprising that Greaves was unable to find a distributor in the late 1960s and that the film went virtually unseen until it was resurrected in a 1991 retrospective of Greaves' work at a Brooklyn art museum (Greaves actually tried to leave the film out because he was convinced at that point that it was no good). There is something immediately compelling about the multiple stories, whether it be the feuding couple or the feuding filmmakers; both are reflections of each other and symptomatic of the way in which people and their environments interrelate. Even though you're never sure of exactly what is real and what isn't, when people are "acting" and when they're just "being themselves," Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One has a rare immediacy that draws you deep into the illusion even as it forces you to question every bit of it.

Copyright © 2020 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information